Even though this year they had to cut short their August holidays to come back for the harvest. Not so long ago, certainly in the lifetime of most vignerons, five good harvests every decade was a happy average. Part of the reason Champagne as we know it even exists was the perennial problem of what to do with unripe fruit grown in those very northern latitudes.

Lately it's been one bumper vintage after another, usually great quality and decent enough (perhaps too generous) quantities. Suddenly the region and its producers have been faced with a number of unlikely challenges: the Prosecco Wave has cost them volumes at the same time as Covid has reduced the opportunities to consume a drink whose primary market remains celebratory occasions. There's a stock overhang, and it's not because what's waiting to be sold is in any way inferior. Since stock and price manipulation is what the regional associations exist to manage, the current crisis created the longest running deadlock between the interests of those who grow the fruit and those who want the region's marketing to be “as orderly as possible.”

But there have been other, less visible, effects which have played a key role in the evolution of the top end of the Champagne market. Several interviews and discussions with Jean-Baptiste Lecaillon, Chef de Cave at Champagne Louis Roederer, reveal the extent to which the game has moved on - providing whoever is in charge of the vineyards and the cellars is free to act without trying to meet the demands of dividend-hungry shareholders.

Here are some of his insights (quoted on Jancisrobinson.com)

“At Roederer the proportion of Pinot Noir has been increasing because the variety is less affected by climate change than Chardonnay. So while Pinot Noir can be picked at only 88 days from flowering, Chardonnay needs well over 90.”

“Why is Cristal released earlier than other prestige cuvées? With Cristal we never aimed for autolysis', I use 40% less yeast for Cristal than for Brut Premier because I don’t want too much autolysis. Because of the poorer viticulture that has predominated in Champagne (high yields, low ripeness, etc), there has been this idea that you need to build the wine in the cellar via autolysis. But this isn’t necessary if you have great raw material.”

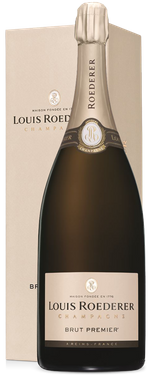

Champagne specialist Tim Hall interviewed Louis Roederer's chef de cave Jean-Baptiste Lécaillon in Reims, where he had just returned from collecting multiple awards on behalf of the house at the Champagne and Sparkling Wine World Championships in London. These included Supreme World Champion for Roederer's Brut Premier NV in magnum, which was also named Best French Sparkling Wine, while Cristal 2002 was Best De Luxe Champagne.

"[2018] was a beautiful year. But when you have such perfect conditions you also have, it seems, more winemaking options..... You are not compensating for shortcomings in the grapes, you are making the best you can from the best there can be. There is a great responsibility to express what the year presents you with."

"You can say you want to make a 'house style', ... In a vintage like 2018, and this is why it is exceptional, it is not what you want, it is what you have."

"So, you need to position yourself, not as a traditional champagne house or winemaker and say 'I want to make a Roederer style wine', but quite the opposite, and you need to say let the vintage speak."

"I believe great vintages come when the full cycle of the season is allowed to go to its natural end..."

"Low acidity does not worry me. All the great vintages of Champagne are low acid. ... There is almost a correlation, low acid: great vintage. Acidity became an issue in Champagne only with the arrival of stainless steel in the 60s. ... As soon as you shift to stainless steel there is no more 'sucrosity' and richness from the oak and its lees contact ... Malolactic became a tool to add richness, texture and flavour ... It became the epochal signature of champagne in the 70s and 80s and everyone thinks when you speak of malolactic it is a question of acidity.... It is not so much the acidity that is important, it is the creaminess and roundness that you get. It's as much about texture and weight as controlling acidity."

"I think we may go back, in the future, to picking early but picking very ripe, soft grapes....Champagne's challenge is not low acidity under climate change but how, without or with less malolactic, it is going to create a new flavour profile under pressure from climate change."

"This is a big question when we come back to global warming or climate change. If you have poor viticulture, with herbicides and not working the soil, not devigorating with some green cover crops, then the juice is diluted and if you then block malolactic, you are dead; you make battery acid.”