Anthony Hamilton Russell is a gentleman. There are different definitions of a gentleman, originally meant as the common denominator of gentility, the term has evolved to represent a standard of BEING. There are many facets to a gentleman, and it is my belief that Anthony embodies most of these. First, there are the aesthetics of a gentleman, though superficial, indicative of something more. He wears a selection of hats collected from around the world and is generally very well turned out in any scenario. He loves Cuban cigars and is an avid collector of these - in fact, he sits smoking a cigar while conducting this interview and I imagine him any day of the week pouring over papers in his study like this. He is a fascinating conversationalist, with interests ranging from 100-year-old Tortoises (Agatha roams the grounds at Braemar) to soil analyses, and Faulkner. He is a spiritualist and you can find tokens of this throughout the estate, each room contains a horseshoe for good luck, and he carries a small wooden cross from St Patrick’s cathedral in New York in his pocket to touch wood when the occasion demands. His house and grounds are filled with objects of provenance, thoughtful things that MEAN something to him, a true collector (or Taurus). While these THINGS do not make the man, they do however tell a fascinating story ABOUT the man. As Haruki intimates, gentlemen have responsibilities. You see Anthony is a very strategic man, with a background in biological science, finance, and geography, he sees the BIG picture and carves out relevant objectives, not just for himself, but for the greater good of the people and area around him.

Responsibilities

In an argument, people sometimes say: “Yes, but YOU’RE not my responsibility.” Or “How you experience that is NOT my responsibility.” I, therefore, find it admirable when people seem to accept MORE than their responsibility when they actively try to better things for the people around them. As such Anthony has taken responsibility for several BIG objectives, including the designation of the Hemel-en-Aarde appellations (Hemel-en-Aarde Valley, Upper Hemel-en-Aarde Valley, and Hemel-en-Aarde Ridge); the pioneering of said appellations and the founding of the Hemel-en-Aarde Winegrowers’ Association; his fascination with Pinotage as a cool climate grape and his constant lobbying for its place amongst the best wines of South Africa; his support of previous Hamilton Russell Vineyards winemakers such as Peter Finlayson, Kevin Grant, and Hannes Storm (who now makes Pinot noir from all three appellations); his efforts in maintaining the natural fauna and flora of the area by working to establish an unbroken band of conservation around the Hemel-en-Aarde area in conjunction with his fellow Hemel-en-Aarderers; and even his assistance of long-time employee Berene Sauls in establishing her own brand Tesselaarsdal with the help of HRV winemaker, Emul Ross. He tells a funny story of Eben Sadie, having told him that he felt Pinotage had an exclusively old South African wine industry identity which could possibly compromise its appeal abroad, and Eben responding candidly: “Ja, how do you tell a crocodile it has a long face.” For his love of Pinotage he established neighbouring Ashbourne in his trademark two wine style, the one, of course, a home-grown Pinotage and one he hopes will someday be seen as one of the most awarded expressions of our native grape. Southern Right, his third wine brand, yet ANOTHER Hamilton Russell neighbour, enjoys great acclaim abroad, also featuring a much loved Pinotage in its two wine range. And these are merely the BIG things, Anthony is father to four girls, and he and his wife Olive are also producing a Pinot Noir and Chardonnay in Oregon - but I’ll tell you about that later. The point - Anthony is a man with BIG aspirations and responsibilities, which he performs in a decidedly gentlemanly manner.

40 Years

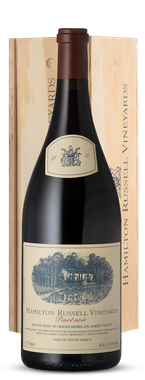

This year marks the release of Hamilton Russell’s 40th Vintage - with Anthony at the helm for 30 of those years. His father, Tim Hamilton Russell found the farm, with the help of Desiderius (Deso) Pongrácz in 1975, and bought it from a struggling livestock farmer, at a time when there were no vineyards in the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley. Tim had first tried to purchase Muratie in Stellenbosch, but then owner Anna-Marie Canitz would only sell to a Melck, and she did, when Ronnie Melck finally approached her. It was a daring thing to do, but Tim Hamilton Russell, an advertising executive all his life was a daring man by all accounts - he even grew vines in his garden in Johannesburg and made wine from them, and his pioneering spirit seems to have rubbed off on Anthony. Hermanus carried a deep emotional significance to the family, with Anthony’s grandfather owning a holiday home in town where the family celebrated each Christmas. The farm was situated unusually close to the ocean, but with a winning layer of clay and iron-rich soil, perfectly suited to the growing of vines. Tim planted the first vines in 1976, including significant plantings of Pinot Noir, hiring his first winemaker Peter Finlayson from Boschendal in 1979. Several different varieties were planted and by 1991, 10 different wines were being made from these, unknowingly an experiment in regional winemaking. From the first vintage in 1981, the Pinot noir just ‘sang’, though it was Anthony who decided to focus their attention on Pinot Noir and Chardonnay exclusively in the 90s. From 1991, he set about removing all the Swiss “ champagne" Pinot Noir clone, BK5, and replacing it with a selection of Dijon clones. By 1998 they had replanted a 100% of their Pinot Noir vines. When Emul Ross joined the team as winemaker in 2014 in the build-up to the 2015 vintage, they had just made the move toward organic farming. Emul started using more dialed back oaking - now with their own specifically tailored light toast by cooper Francois Freres for a purer, cleaner, expression. They have still retained their trademark muscular, spice-driven Hamilton Russell character, a function of the site and soil and not a result of working the caps hard. I love the way Anthony describes the 2020 vintage Pinot noir: “ It doesn’t have massive palate weight, but still has an athletic structure. Tightly wound tension - suggesting it will age well. This is a hard-to-understand wine, an intellectual wine, you’ve got to sit with it, it demands something of you, and you, in turn, need to judge it for its potential.” To me it sounds like a poem about a sage teenager, debating with his elders, a representation of THEIR future, and his, an evolution challenging the status quo. Anthony continues: “unlike a typical vintage, it’s more Côte de Beaune, than Côte de Nuit - Volnay meets Pommard.” He says this vintage is a throwback to the wines of the early 80s, with remarkably low alcohol levels, despite their phenolic ripeness the Pinot noir, and Chardonnay both come in at just under 13%. Of the Chardonnay, he says it’s true to the terroir, with pears and lime, not tropical fruits, and a mild whiff of egg-shell reduction - spot on. We talk about his love of Burgundy and he explains that his particular tastes are focussed on old, structured wines from marginal vines: “I like the kind of primal aspect of it, the old mankind smells, it plucks at all your ancient genes. You get that in old Burgundy. Old Bordeaux reminds me of a seashore after a storm, very marine in its profile, while Burgundy is old mankind. It feels PRIMAL. It tells you the story of a site, that you can’t unlock in any way other than through that grape varietal.” He says he enjoys a good red Burgundy at around 20 years old, while he personally likes Hamilton Russell Vineyards Pinot Noir with a decade or two in the bottle, however enjoyable it is from day one.

South African wine in a nutshell

I routinely ask my subjects what they think the strengths and weaknesses of the South African wine industry are and how it has evolved since they began. Anthony offered unique insights in his characteristic BIG picture way. The strengths of the South African wine industry he says are as follows: South Africa was never meant to be a low-cost producer of wine. We had too many endemic issues to solve with our communities and labour and even the yields of regions such as Robertson, Wellington and Paarl were never really as high as the yields of our top New World competitors. We are also less well capitalised and mechanised and the cost of debt is high. Thus, pure free market forces have introduced a shift, we’ve started focussing on making less wine, but better wine - with more small producers, making wines from niche terroirs, that have more aesthetic appeal to international fine-wine lovers. The opening of the export markets after the abolition of apartheid had also given us a much-needed ‘hup-stoot’ - allowing us access to bigger, wealthier markets and stronger currencies to facilitate the making of these smaller, boutique wines. Anthony says that in the early days we tried to emulate Australia and their tremendous success in the UK in particular, with BIG fruit, and often oak-driven, varietal wines in even BIGGER quantities. In recent years, he says, we’ve aimed for more elegant wines with the finely attuned aesthetic of our new generation of winemakers, not trying to be everything to everyone, having moved away from what he terms ‘Australia-ness’. Additionally, the diversity and freedom of South African winemaking have allowed us not to be pigeonholed - we produce incredible Bordeaux-style blends, incredible Cabs, incredible Syrahs, incredible Pinot Noirs, and truly great Chenin blanc at many different price points unlike our New World competitors - and perfectly play into that small, boutique wine mentality, with winemakers experimenting and exploring and PIONEERING areas and varietals in previously vinously unexplored regions. Making South African wine EXCITING in a way only we can be…

The Plan

Of weaknesses, we know there are many - but I found his summary of them almost like a plan of action. Firstly, he says there are not enough winemakers on planes. Hamilton Russell Vineyards is in a lucky position, selling in 60 countries around the world, because our South African market is small in world terms and because it is important to get our names out there for all South African wines. Marketing isn’t a team sport or even a FUN sport, but a necessary one. Winemakers and Estate owners need to be pounding the pavements around the world as marketing is about relationships and it’s a hard job, sometimes thankless, but if you’ve read anything of successful entrepreneurs, it is the unstoppable energy spent examining EVERY avenue that results in success. Secondly, when making award-winning wines, we need to make them in relevant quantities. While limited quantities and the absolute RACE to attain a few bottles are exciting to some, if there’s not enough to go around, the market stays limited and the brand hidden to most consumers. Thirdly, we don’t have enough large, professional high-end players - while small boutique wineries are our image bread and butter we need powerful high-end entities to drive the market for premium wines and create opportunities for smaller producers to grow. Fourthly, our local market for premium wines is small, making it necessary for us to look abroad - though Anthony usually sells close to 50% locally, the global pandemic meant he needed to sell a lot of the local allocation internationally, and could. Fifthly, our failure to properly communicate appellations and styles in relevant ways makes us miss out on the most interested wine buyers. Anthony’s purpose in designating the three appellations of the Hemel-en-Aarde is not only an exercise in precision but a high-level marketing initiative appealing to high-end consumers interested in the nuances of New World terroir producing, at times, distinctly Old World wines. The more precisely defined, the easier to sell to a discerning clientele. Lastly, and classic Anthony, is the agricultural law prohibiting the sub-division of vineyards into smaller units. This means small-scale winemakers are unable to purchase land because the law doesn’t acknowledge the agricultural viability of what can be even very small areas of vineyard. Where livestock and grain farming require large tracts of land and become ineffective when sub-divided, vineyards do not have this limitation. If young winemakers are allowed access to owning a few rows of a famous vineyard, or a small plot in a defined wine area, this vested land interest may very well see the proliferation of small wine brands with integrity and a better ability to borrow. Anthony says he’d love the law to enable this in the industry - for the government to identify pockets of wine-growing land and allow sub-division with the understanding that you must keep that unit viable and devoted to viticulture. Having it laid out in these broad strokes - it all seemed so ATTAINABLE, no?

How to Fail

One of the premises of Rooted is how failures have produced success. Let’s face it, we’re all a bundle of failures and struggles that have shaped our response to the world and our understanding of ourselves. Anthony says that having the courage to try and fail is fundamental, or rather the courage to LEAD. He says that Emul demonstrates this courage while not representing HIMSELF, but his team, his close and constructive relationship with their viticulturist one of the key factors in the success of the wine. Anthony says he’s failed at a lot of things - one of these, Birkenhead brewery, which he started with partners in 1996, still in existence though Anthony is no longer a part of it. He says it was a financial failure and he had to pay his way out. What he learned however was fundamental: “I’m not good at financial partnerships and I also don’t really like beer - don’t make something you don’t really love.” He also talks about his failure to focus with the Ashbourne range - making a single vineyard Pinotage into a blend, in an effort to try and differentiate it from Southern Right Pinotage. He has since gone back to the single vineyard Pinotage and has learned that the marketing concept can’t drive the whole concept if the wine isn’t up for it. I think Anthony’s ability to fail and self-correct, and move on, and not to be defined by any one thing - except perhaps his will to contribute and innovate - is HIS superpower.

Oregon

As if three brands and a whole host of other concerns in South Africa weren’t enough, Anthony and Olive also make wine in Oregon, USA - though with a South African twist. Graham Weerts, a fellow South African and winemaker of Capensis in SA and head winemaker for the American Jackson Family proved to be the link to top Oregon Pinot and Chardonnay sites. Emul flies over every harvest and makes the wine there in minuscule quantities - 400 cases of 12 Pinot and 160 cases of Chardonnay - only sold in the US. Though the Hamilton Russells also have a very strong base in the US for their South African wines, Anthony is vehement in professing his deep commitment to South Africa when it is suggested that the US may be a bolthole from South Africa should things get impossibly tough here. The mark of a true South African.

Kanniedood

“There’s no way I’m going. Even if I have to live in a string vest and drink beer.” Anthony says he loves meeting South Africans throughout the world. We’ve had to think more deeply about many issues than most people in first world countries, we’ve learned to be hardy and resourceful to survive - in a sense we’ve LIVED more than most as a nation. He says in essence his passion is for a 52ha, Northeast facing bump of really old clay and iron-rich soils - their “monopole”. “That’s everything to me - that’s my life’s work. I’m experimentally intrigued.” He’s farmed it now for 30 years, and his father for 15 years before that. He’s had a RELATIONSHIP with this place and is expressing it through the wine. If you think about it, don’t we all want to SHOW our passion for something, someplace, or someone in a meaningful way? Don’t you wish you had such an outlet? In the end: “I can’t put this in a suitcase, I can’t ship it anywhere else, it has to be here.” And because it IS here, the gentleman remains to take up his duties and further the cause. OUR cause.