They don’t REGISTER struggle. They assess it, fix it, and move on. Case in point, Charl du Plessis of Spice Route, now in his 19th vintage, highlights the drought and the economy as HIS struggles, though not REALLY a struggle as he’s already addressed it by going organic, making natural wines and reworking his expectations. “Verder het ek nie issues nie…” / “Further, I don’t have any issues.” Jis, I love them (winemakers)! Psychiatrists would have a hard time making money out of THEM.

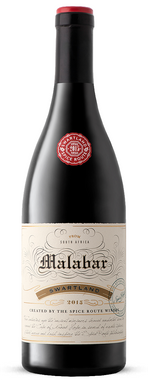

Now, you’d be forgiven for thinking that Spice Route is the sprawling enterprise in Paarl. That is Spice Route THE DESTINATION. The distinction is very important given the huge disparity between Spice Route THE WINE and Spice Route THE DESTINATION. Don’t get me wrong, I love Spice Route THE DESTINATION, it is a beautiful hub for artisanal producers, be it chocolate, gin or beer. It makes the wines of Spice Route, from an obscure, unmarked farm in the Swartland accessible to more people, creating the illusion of commerciality, when in fact these wines are RARE, obscure even. Let me explain.

GPS Co-ordinates

I was given directions to the farm ‘Klein Amoskuil’ as GPS co-ordinates, with a screenshot of the unmarked entrance for reference. I’m not very good with GPS co-ordinates, I sent Kleinjan the photographer around 20 minutes North of there…he was unimpressed. Following the backroads of the Swartland, along a seemingly abandoned train track, (don’t they all seem abandoned?), I came across a huddle of unassuming buildings, beautiful in their neglect, as if an interior designer had made the walls discolour just so, and painted all the doors a periwinkle blue reminiscent of the French country craze, now seemingly just right. An abandoned old farmhouse stands to the side, its window and door frames painted the same periwinkle blue, the outline of a fish, the 'Jesus fish' stuck in one of the windows - funny, given that the last occupant of this house was Eben Sadie, when he used to be the winemaker at Spice Route in 1998. {Charles Back purchased the property in 1996.} No-one lives there now, but there’s purpose here, the fish says so.

Benign Neglect

Charl Du Plessis took over from Eben Sadie in 2002, Charles Back apparently having had his eye on him for a while as the first winemaker at Rijk’s in Tulbagh. Charl always wanted to become a veterinarian, though he quickly changed his tune when he figured out how many years he’d have to study. He’s literally been making wine now for 28 years, 19 of them at Spice Route, a time during which he says he’s completely revised what he knew about winemaking. You see, Spice Route is different. It’s been completely organic for three years now, and in 2018 took receipt of 10 Qvevris, some of the first of their kind in South Africa, though not officially THE FIRST. Made in the “cradle of winemaking”, the East European country of Georgia, with an 8000-year legacy to back it up. Qvevris or ‘Kvevris’ are conically shaped fermentation vessels that are buried in the ground, in which grapes are basically left to ferment, stems and all (sometimes without stems), punched down 4 times a day and (in Georgia) left on the skins for around 6 months to produce their trademark amber wine (if white) with its tannic grip. Not to be confused with amphorae, which, while also conically shaped and made of clay, are kept above ground, and were originally used as transport vessels, though also well-suited to the task. The Qvevris have since multiplied to 20 and are housed in the beautifully neglected cellar, with its stained gable, and strangely ostentatious chandeliers. The benign neglect of the natural wine, seemingly reflected in its surroundings. Charl says he is particularly interested in the white wines made in this manner, specifically because of their beautiful amber colour, and because red wines are usually fermented on the skin for a period of time anyway and therefore the flavour profile is not as different from what we’re used to. Given the musty character of traditional Georgian wines, Charl has been conservative with this skin contact, initially only limiting it to 6 weeks rather than the prescribed 6 months, though he has been experimenting.

Innovation

I think that is the defining characteristic of this farm and brand, innovation, but not in the pristine lab coat kind of way, rather working backward, back to nature, back to historical techniques, doing less to achieve more. Charl I think has been the stabilising factor, encouraging Back to limit the wines produced here to wines with a real sense of the Swartland. Though he does share Back’s love of the unknown, having recently been successful in planting, and this year experimenting with a French grape, Petit Manseng. He even succeeded in getting SAWIS to add it to our list of varietals- an arduous process in itself. It is a white cultivar with very high natural acidity, well suited to the Mediterranean climate of the Swartland, which stands to beautifully balance out the white Obscura blend - to be revisited in a few years. When I asked Charl what his big milestones were, he didn’t reference any awards or accolades but referenced the wine. The Chakalaka, a 6-way Mediterranean-style blend. ‘Mediterranean’ and not ‘Rhône’ because of the inclusion of Tannat, making this an authentic Swartland blend, its success indicative of how GOOD it is and the Swartland’s predisposition for iconic blends. He also spoke of retaining the oldest Sauvignon Blanc block in the country, the Amos block, planted in 1965. What’s interesting is that while Sauvignon blanc might not be a varietal you associate with the Swartland, the sheer age of it and the resulting root systems have meant that this block survived the drought even better than any of the younger “drought-resistant” varietals. In the end, Charl says he makes the wines that the Swartland allows. With the absence of a mountain, its aspect, micro-climates and such, Klein Amoskuil is well and truly at the mercy of the elements, which in a sense has forced Charl to take the organic route and grow grapes that would survive here, though he says he would have loved to make Pinot Noir he’s resigned himself to ‘play to their strengths.’

No Tears

When I asked Charl why he makes and STILL makes wine in South Africa, there’s none of the usual ‘onwards and upwards’ talk, there are just hard facts. The potential of South Africa as a wine-producing country, the diversity of it, the quality of it - how could one not? The potential far outweigh the cons. As I drove away I contemplated the fact that I didn’t get what I thought I would get, I mean you’d think the harsh conditions of the Swartland would elicit some sort of emotional response, a sense of perseverance hard-won grit, blood, sweat, and tears. But there are no tears to be shed here, sweat maybe, but its as if the people of Spice Route embrace the struggles of making wine in the Swartland, in fact, they don’t register it as a ‘struggle’, merely part of their plight in making authentic South African wines in celebration of its terroir. You really should try the wine.