The prices of trophy wines – like those of “collectable” works of art - produce the same shock, horror and outrage every time there's an obvious disconnect between middle-class reality and what someone for whom these are frivolous purchases is prepared to spend. Think of the publicity which pursued the yuppie bankers whose wine bill in a smart London restaurant came to R800k, or the reaction when the $1.4m Banksy self-destructed the moment it was sold on auction. This isn't a coincidence – wine shares in common with art the absence of any readily available tool to determine value, since appreciation of both is subjective. As with art, established icon wine brands have a known price in a known market. But this is merely an indication of what someone will pay in order to own what has suddenly become a “must-have.” It's not the same thing as a quantity surveyor working with a set of architectural drawings to prepare a costing of what you will need to invest to build a new house (or even to estimate what someone else spent on a structure).

With wine, as with art, what is paid depends on how badly the trophy is “needed.” If there's no hunger to own it, it has no value. If you don't care about the aesthetics of decorating your home you can cover the walls with pretty pictures for a fraction of what it would cost to buy a signed reproduction produced by a well known (in other words, branded) artist. If you don't get the nuances of a wine (or the nuances of wine snobbery) you can still enjoy a perfectly acceptable and drinkable beverage for less than 1% of what you would have had to pay for a big name bottle from the same vintage. Same amount of fluid, same amount of alcohol, pretty much the same colour in the glass.

A De Ladoucette Pouilly Fume from the Chateau de Nozet's cellars will cost you between R500 and R600; Dagueneau's Silex probably three times this amount. In fact it's hard to imagine sauvignon blanc from any where in the world fetching more than R2000 per bottle – so when you discover that Screaming Eagle Sauvignon Blanc (which is not the wine on which the cellar's reputation rests) regularly trades for over R80k per bottle you realise that price here serves the role of a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Screaming Eagle has long been famous for its red wine. Right-minded consumers should know better than to imagine that simply because a cellar enjoys a reputation for a certain style/colour of wine, the competence/cachet transfers easily. This is no different from Landrover launching a two-seater high performance cabriolet on the strength of the Defender's reputation as a bush-whacking vehicle. What Screaming Eagle has managed to do is use short supply of the white wine to lift its price point above the cellar's better known and more traded red. When money is chasing status, not taste, what lurks inside the bottle makes very little difference.

Fifty years ago a bottle of Romanée-Conti sold for less than R20. Today a current release vintage will typically sell for more than R250k. This reflects a 12000 fold increase over half a century. Is the 2015 that much better than the 1964 – both are legendary vintages, separated only by time and technology? There's no doubt that the 2015 will be a better wine – the Domaine manages its vineyards now more thoughtfully than it did forty or fifty years ago, but you can bet that this question is of no concern to the oligarch buying a trophy wine to impress his guests.

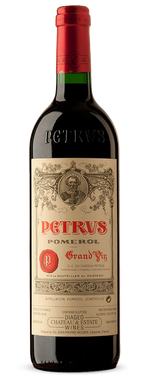

From this it should be clear that once a producer has recovered on the actual production cost of a bottle of wine, the determination of its selling price is purely arbitrary. This doesn't mean that every producer in the world is free to set price in flagrant disregard of what is going on in the market place: if you have 1m cases of wine to sell, no matter how much you think them worth the price of a bottle of Romanée-Conti, there's no point in using R250k as your opening offer. If your wine is exceptional, enjoys widespread critical acclaim, is produced in minuscule quantities AND you have deep enough pockets, you might be able to hold out till you get your price. This is exactly what the late Mme Loubat did, insisting (when no one even knew where or what Petrus was) that it must be priced alongside the other First Growths. Even this did not happen overnight: in 1945 it sold en primeur at half the price of Lafite; by 1961 (the year she died) it hovered around the Lafite price – a situation which prevailed well into the 1980s before it surged ahead. In other words, it took almost 50 years for Petrus (with less than 10% of the production volumes of Lafite) to pull clear of the other top Bordeaux growths, and to maintain its pricing superiority. Positioning, with price as a proxy for quality, is not an overnight solution to wine marketing.

So when a bunch of our leading winemakers sit around and talk about how South Africa needs icon wines to help reposition the image of the Cape as a fine wine producer, they're not wrong. Mme Loubat showed the way – though it's worth remembering that she did so when there wasn't all that much competition in the market, and at a time when Bordeaux occupied the very pinnacle of the pyramid. Half a century from now, if all goes well, a few of them should be quite securely positioned somewhat further up the slope than they are today. They could even succeed in dragging up the image of Brand SA in their slipstream.

However, it won't be a quick fix, and it won't come with the unquestioning acceptance of those who have to buy what they are trying to sell at ever-inflated prices. Despite the difficulty of calibrating value when it comes to wine, the old adage holds true: you can't fool all of the people all of the time. The human brain is a truth seeking device when it's not clouded by the need to gratify the ego. Blind tasting separates the aspirations of the producer from the wilful self-deception of the consumer. Everyone should try it, from time to time.